By Agnessa Spanellis

I quite often have to explain the concept of gamification to those who know very little about it. Although they intuitively understand that it has something to do with games, still the term is quite ambiguous. It does not help that it went through a hype cycle in the early days and did not deliver up to its promise. For the most prominent criticism, you can read the writings of Ian Bogost (2015).

The concept is the most recent addition to the cluster of related and overlapping concepts on the game-play spectrum. Since it started being widely discussed in both industry and academia (around 2010), the interpretation of the term has evolved. I became interested in the concept of gamification around the same time, and my understanding of it has also evolved as the term developed and my first-hand experience grew.

It is no wonder that the whole family of concepts can cause considerable confusion. In this post, I will try to put in some order the overlapping concepts of gamification, serious games, play, gameful and playful design, and others, by reflecting on my projects and examples of other interesting projects I have come across in the past years. Let us start with a formal definition.

Gamification has initially been defined as the use of game elements in a non-gaming environment (Deterding et al., 2011). The focus on game elements rather than complete games emphasised a distinction with serious games, as the concept started growing in popularity.

Let us look at example 1: gamifying performance management. Warehouse staff are split into teams. Each team has a target of a number of boxes they have to pick for delivery by the end of the shift. The teams can track their progress on a board, where the forklift-shaped magnets move along the progress bar to indicate how close each team is to achieving their target. In this example, the workers are doing their work. The gamification layer added to their performance management system does not look like a game, but we can clearly recognise game elements: the teams, a progress bar, a clear end goal and team competition dynamics. So far so good.

Here is example 2, which has more resemblance to a game (Spanellis et al., 2022). Client facing staff are split into teams, each of which represents a ship embarking on a journey in search of golden treasures. Each ship has a captain (a division manager). The distance they cover is calculated based on the number of contracts closed along the way. They encounter quests, for example, having to pay ransom for their kidnapped captain by completing a new training, or discovering new islands by developing new partnerships. In this example, the whole experience resembles a game. There is a theme and a narrative. There are quests, clear rules, roles, and a win state. Still, employees don't actively play a game as a distinct activity. Rather, the game unfolds as the players complete their job tasks. Therefore, this example still fits in with the gamification definition.

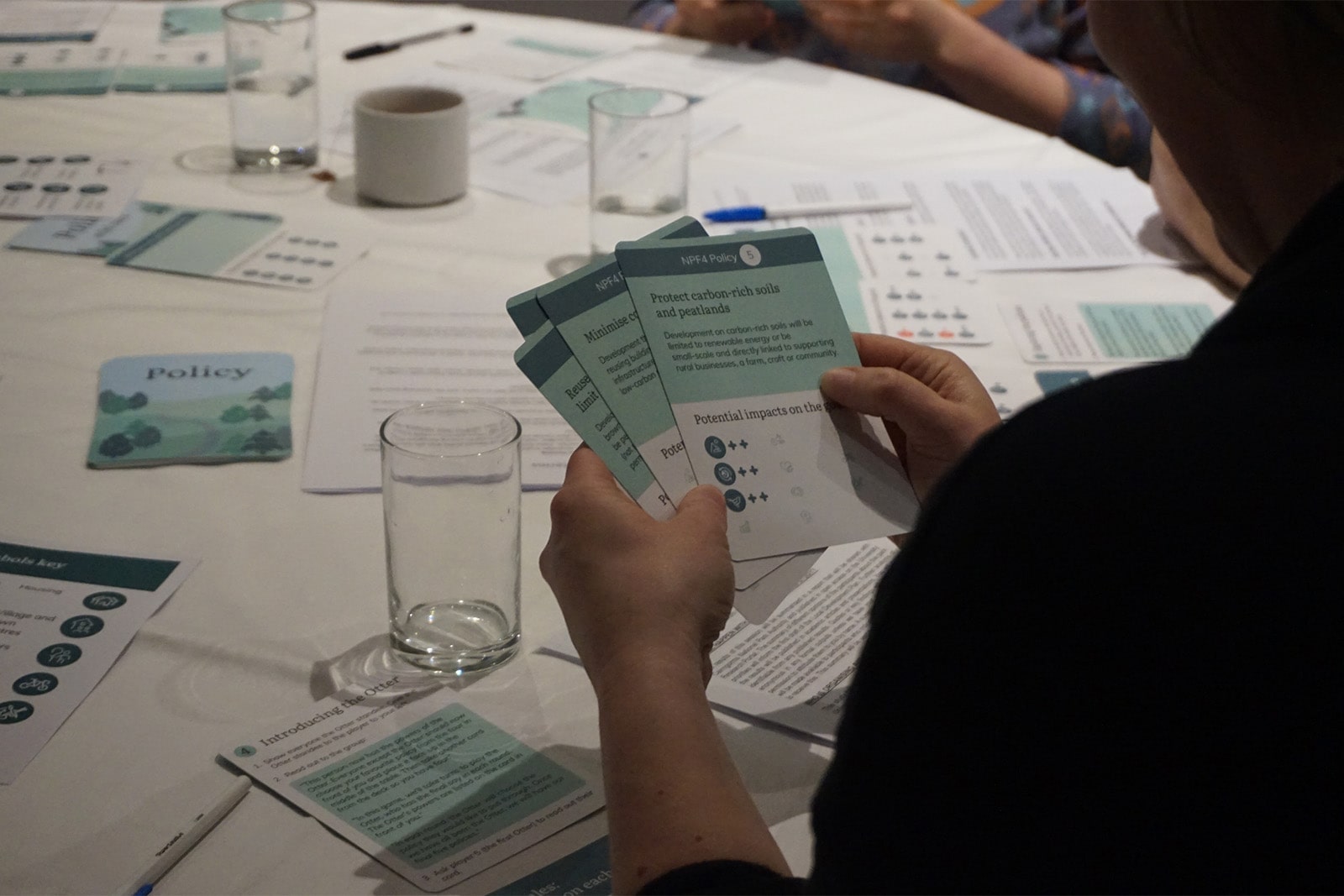

Let us look at example 3: public consultations meet gamification and AI. Local residents are invited to participate in a public consultation to provide input to a local development plan that is due to be updated in the next year by National Park authorities. At the consultation, they are invited to sit around the table in groups and play a card game. The card game offers them to step into the shoes of policy makers and develop a policy proposal from the available policy options that are captured on the cards. The game offers a structured way for discussing and selecting policies in each round. The conversations that happen around the table are captured and used as evidence by policy makers. In this example, we deal with an activity that has a clearly recognisable game structure and requires participants to “sit down and play”. Some would argue that it is not a gamification intervention, but a serious game. So, what is a serious game then?

Serious games from their name assume that a created environment is something that one would recognise as a complete game. They primarily have an educational purpose (Abt, 1987), which has been broadened by some scholars to a utilitarian purpose (Alvarez et al., 2023). However, entertainment is also seen as an essential component, hence serious games overlap with entertainment games. And some argue that all games are serious and the term was invented as a marketing trick (Laamarti et al., 2014).

The overlap with gamification occurs when a gamified intervention resembles a game, but its purpose and context are debatable. In example 3, the activity that the participants perform is a form of public consultation, whereby citizens express their opinion about different policies, and it just happens to be in a form of a game instead of a townhall meeting. And therefore, there are grounds to call it a gamification intervention. Reflective of that, the interpretation of gamification has evolved and now includes games alongside game elements applied in a non-gaming context (Hamari, 2019).

The underlying reason for differences in understanding and overlaps between the two might be in the focal point of attention. Gamification focuses on the practice and context in the real world, what is being gamified. If it happens to look like a full-fledged game, so be it. The interactions between game elements and the practice are of more interest than the game design. Whereas, serious games focus on the deployment form, how game principles are being applied and what qualities the game carries. The context is secondary.

Let us look at example 4: building natural barriers for flood protection in Suriname. Representatives of different interest groups are invited to a workshop to discuss different strategies for coastal protection. As part of the workshop, they are invited to play a game whereby as a team they are asked to manage a coastal line of a fictional country, while also looking after different aspects of its economy. They are offered to implement different coastal protection strategies, each of which has its maintenance requirements, level of protection and related costs/benefits associated with it. At the end of each turn, the team is faced with an event that tests the resilience of their strategy through the game. The players have an opportunity to learn about the science behind different strategies and related natural processes. They can seek for more knowledge and “unlock” bonuses with additional knowledge cards.

One of the primary objectives of this game is to invite the stakeholders to learn about “science behind” and interconnectedness within the system so as to help them to have a more informed discussion about coastal protection strategies. The other important objective is to facilitate consensus building among stakeholders by exposing them to diverse and sometimes competing needs. In other words, this example focuses on supporting the development of conditions towards building consensus, which includes helping them to develop different facets of knowledge, such as cognitive, experiential, and relational knowledge. All this requires a serious game to develop. However, this case also seeks to create a safe space in which a constructive debate can occur. We could call for different stakeholders to meet for a round the table discussion, however, this is likely to lead to an emotionally charged debate with slim chances of reaching consensus. Instead, this example offers a gamified space that is self-regulated through the characteristics of the game, and thus provides the necessary psychological safety for consensus-building to have a chance. Hence, gamification researchers have reason to call it an example of gamification. Examples like this are very difficult to distil and maybe they do not have to be a clear cut.

Two other concepts that have been introduced to classify other related phenomena in gaming refer to serious re-purposing and serious modding. Serious re-purposing refers to the phenomenon of using an entertainment game for serious purposes (Alvarez et al., 2023). We can find many such examples in healthcare, whereby entertainment games are used with patients because playing these games helps to achieve specific therapeutic outcomes. For example, video games have demonstrated effectiveness in preventing or mitigating cognitive decline in elderly patients (Wang et al., 2024).

The concept of modding takes it one step further. Serious modding refers to modifying an existing entertainment game to give it a utilitarian purpose other than entertainment (Alvarez et al., 2023). Although the practice of modding is not limited to serious purpose, serious modding defines a subset of modding practice, whereby the modification serves a non-entertaining purpose. An example of a game that has “inspired” numerous modifications is Monopoly. Alongside entertainment versions of this game catering to different audiences, there are also versions like Homeless Monopoly to raise awareness about homelessness, and Commonspoly that promotes collaboration and protection and sharing of common goods and resources.

Up to this point, we have been talking about playing games. What about the instance of play? Is there a difference?

In game studies, the researchers differentiate between games and play that ties back to Caillois's (1961) distinction between paidia (a more expressive and free form of playing) and ludus (rules-based playing), which is associated with games. This distinction is useful because it helps to recognise other forms of play and playing that do not fit with the above definitions and examples. For example, if someone brought a toy horse into the office and others followed suit and turned the office into a zoo full of stuffed animals, this is a distinctive form of behaviour which is independent of other activities that happen in the workplace and are connected to work responsibilities. It is distinctive from what would be considered an ordinary or real office life, and it is a freely chosen activity which does not bring immediate rewards or have a clear win state. In many ways it is similar to how children play with toys.

However, you are likely to come across other forms of play, that is playing games as a form of distraction in the workplace. This is where confusion with gamification might occur. While gamification is embedded in the activity or in some ways replaces it, like in example 3, the activity of playing a video game is distinctively separate from performing a work-related activity. This is an important difference that can help to recognise different phenomena in the non-gaming environment and choose appropriate approaches to studying them, which might also be different.

Next, you might also come across the terms of playful and gameful design, sometimes used quite liberally and interchangeably to denote anything game or play related. An attempt to draw a conceptual distinction between playful and gameful design (Deterding, 2016) draws on the distinction between paidia and ludus discussed earlier. Playful design affords experiential and behavioural qualities of playing, while gameful design affords those of games, which is achieved through the means of gamification.

Let us look at example 5: piano staircase in Stockholm. In 2010, Stockholm started experimenting with using fun for behavioural change, where in one of the experiments a staircase in a subway station was transformed into piano keys. Through what looks like a playful design, commuters were invited to engage in the activity of “playing the piano” for the sake of the activity without an evident purpose or end goal. And therefore, this experiment looks like an example of playful design. However, the designers of this experiment had a purpose of prompting the commuters to choose stairs over an escalator. Thus, if we widen the boundaries of the system and include designers and their worldviews, the design, that is the representation of the system, has a purpose and therefore it is a gameful design.

It is likely that under scrutiny we might find that most examples of playful design will have a purpose (that of the designer), and unless the purpose is discussed narrowly in relation to the “end user”, the distinction between gameful and playful design becomes very muddled and might not be very meaningful. It is also important to acknowledge that definitions evolve with time as we learn more about the phenomena, and so they need re-evaluating on a regular basis.

Finally, let us talk about game theory. It is a common experience among gamification researchers to see people confusing gamification for game theory. But gamification is NOT game theory. Game theory emerged as a field for studying strategic interactions and decision-making. You have probably heard about a zero-sum game, a game in which one player’s gain is another player’s loss. There are other types of games, all of which have one common characteristic—the outcomes for one player depend on the choices of others. Of course, this is common in other games too. The distinguishing feature of these types of games is that they are clean or “sterile” versions of game mechanics void of any context, to study the decision strategies of players in a lab-like environment, free of influence of other factors. For example, two players are asked to set up a market price, which will determine the market share and the size of the profit. No context is provided. The outcomes of the game are calculated based on a simple formula. The game can be played quickly and repeated many times, generating data on how people strategise based on the decisions of others in the previous rounds.

But this type of game is not exactly fun. It does not generate behavioural or systemic change, support learning, help to understand complexity in systems, or give a sense of enjoyment, meaningful engagement or accomplishment at the end. In fact, it has nothing in common with all the other concepts discussed above other than it uses game mechanics.

References

- Abt CC (1987) Serious Games. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC.

- Alvarez J, Djaouti D, Louchart S, et al. (2023) A Formal Approach to Distinguish Games, Toys, Serious Games and Toys, Serious Repurposing and Modding, and Simulators. IEEE Transactions on Games 15(3): 399–410.

- Bogost I (2015) Why Gamification is Bullshit. In: Walz SP and Deterding S (eds) The Gameful World: Approaches, Issues, Applications.

- Caillois R (1961) Man, Play, and Games. University of Illinois press.

- Deterding S (2016) Make-Believe in Gameful and Playful Design. In: Turner P and Harviainen JT (eds) Digital Make-Believe. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 101–124.

- Deterding S, Dixon D, Khaled R, et al. (2011) From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining “Gamification”. In: MindTrek’11, 2011.

- Hamari J (2019) Gamification. In: Ritzer G (ed.) The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. 1st ed. Wiley, pp. 1–3.

- Laamarti F, Eid M and El Saddik A (2014) An Overview of Serious Games. International Journal of Computer Games Technology 2014(1): 358152.

- Spanellis A, Pyrko I and Dörfler V (2022) Gamifying situated learning in organisations. Management Learning 53(3): 525–546.

- Wang Y, Zhang K, Yu H, et al. (2024) Integrating music therapy and video games in cognitive interventions: innovative applications of closed-loop EEG. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 16: 1498821.

Agnessa Spanellis

Lab Director, and Senior Lecturer in Systems Thinking at the University of Edinburgh Business School